Financial governance and digital transformation: defining and managing with impact

- Gabriel Amine Ghalleb

- Jun 17, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 18, 2025

Digital transformation is becoming a strategic imperative for modern businesses. But in a context of economic uncertainty, persistent inflation, and severe budgetary constraints, every technological investment must be carefully considered. Innovations are emerging at a frenetic pace—whether in artificial intelligence, cloud computing, robotization, or new energies—making the financial management of these initiatives all the more crucial. Financial governance thus emerges as a critical lever for the success of major digital transformations: it is what allows resources to be defined and allocated with impact, despite the turbulence.

CFO and CDO: financial co-pilots of digital transformation

The growing complexity of technology means that the CFO can no longer be the sole custodian of digital transformation program budgets. Technologies such as cloud computing, AI, and robotics have technical and operational implications that only an expert can properly assess. This is why IT architects—once confined to technical matters—are now becoming true budget co-pilots. Reporting to a Chief Digital Officer (CDO) who speaks financial language, these architects provide realistic estimates, identify hidden costs, and anticipate the scalability of solutions. The CDO-CFO duo can thus establish budgets that are much more in line with the reality on the ground, with each stakeholder contributing their piece of the puzzle: financial expertise on one side, technological vision on the other.

Realistic and agile budgetary decisions

Collaboration between the CFO and CDO extends beyond initial planning to steering decisions throughout the transformation process. Faced with limited resources and rapidly evolving priorities, this duo must be able to make realistic investment decisions—grounded in budgetary constraints and tangible benefits—but also agile. In concrete terms, this means revising allocations if a project isn't delivering the expected value, accelerating funding for a promising initiative, or suspending a program whose assumptions are no longer valid. By orchestrating these adjustments in real time, the CFO and CDO stay focused on strategic objectives while avoiding financial drift.

Beyond ROI: New Metrics for Assessing Value

To shed light on these trade-offs, it's important to revisit how we assess the value of digital projects. For years, ROI (Return on Investment) has reigned supreme when it comes to justifying projects. However, focusing solely on the immediate financial return of digital initiatives is reductive.

To gauge the real impact of a technological project, it is necessary to adopt a broader reading grid, combining multiple indicators:

ROI & ROO (Return on Investment & Return on Objectives) : ROI measures the financial return, while ROO assesses the degree of achievement of strategic objectives, including intangible or qualitative benefits.

Time-to-Value: The time required to generate value. A project may have a high ROI, but if it takes three years to reap the rewards, is that relevant in a world that evolves in a matter of months?

Cost-to-Scale: The cost of scaling up. A solution may work in a pilot, but how much will it cost if deployed on a large scale? Its long-term economic viability depends on it.

Ability to de-silo processes: assess the extent to which the project promotes the interconnection of businesses and data, breaking down organizational silos to improve overall efficiency.

Effect on business agility: measure how the initiative increases (or hinders) the company's ability to adapt to changes, innovate faster, and pivot if necessary.

Risk of technical obsolescence: consider the sustainability of the chosen technologies. Is a project built on shifting sand (ephemeral technology) or on a solid, scalable foundation?

By combining these criteria, decision-makers gain a more holistic view of a digital project's value. This allows them to fund not just the most profitable projects on paper, but also those that deliver a real competitive advantage and long-term resilience.

Beyond the fixed business case: evolving budgetary governance

In a changing environment, building a fixed five-year investment plan is illusory. The traditional business case, developed at the start of a project and rarely revisited, is showing its limitations: assumptions become obsolete after a few months, unforeseen events go unbudgeted, and opportunities are missed due to a lack of flexibility. It's time to move toward more agile budget governance.

A few key principles emerge to achieve this:

Rolling budgets: Rather than freezing spending for the entire duration of a program, budgets are regularly revised (for example, quarterly) based on results achieved and changes in the context. This allows resources to be allocated as closely as possible to current realities.

Milestone funding: Instead of releasing the entire funding upfront, funds are allocated in stages. Each milestone reached (validated prototype, successful first deployment, etc.) triggers funding for the next phase. This tiered model secures investments by verifying at each stage that the project delivers on its promises.

Dynamic PPM: Project Portfolio Management becomes an ongoing exercise. The portfolio of initiatives is periodically reassessed to incorporate new priorities, discontinue projects that have become irrelevant, and intensify those that create the most value.

With these approaches, financial management shifts from a static mode to an iterative and adaptive one. The company thus retains control over its digital investments, ready to redirect focus as needed, while maximizing the impact of every euro spent.

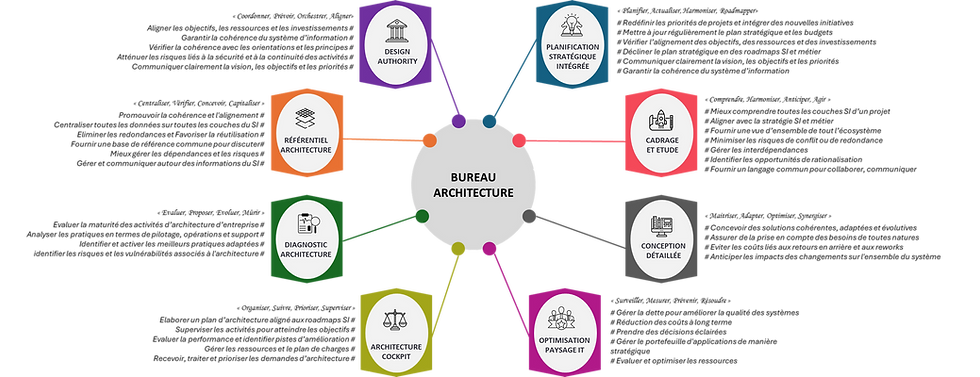

Target architecture and master plan: the investment compass

Finally, a successful digital transformation isn't just about piling up profitable projects in isolation. It's about building a coherent information system capable of supporting the company's long-term strategy. This is where the target architecture and the master plan (the information system roadmap) come in.

These elements should structure investment decisions, not the other way around. In practice, each project under consideration should be confronted with a simple question: does it help move the company closer to its target architecture? If the answer is no, even a flattering ROI does not necessarily justify deviating from the defined trajectory. For example, if the strategic direction is to centralize data in the cloud, funding a new on-premise application silo would be counterproductive, even if its isolated business case appears positive.

By using the target architecture as a compass, the CFO and CDO ensure that every euro invested strengthens the common technological foundation, rather than creating technical debt or duplication. Blueprints provide a comprehensive view of interdependencies and optimal implementation sequences, avoiding the pitfall of investments dictating strategy rather than the other way around.

Conclusion: Governing transformation with impact

Financial governance is no longer a simple accounting exercise in the background of projects: it is becoming their central pillar. By adapting to the uncertainties of today's world, by having CFOs and CDOs collaborate closely, and by adopting scalable budget metrics and processes, organizations are transforming financial constraints into a true strategic asset.

This paradigm shift makes it possible to define and manage digital transformation with impact: every financial decision aligns technology with business strategy, and every euro or dollar invested strengthens competitiveness and resilience. For executives, CIOs, and strategic consultants, the challenge is clear: financial governance must be rethought today to give digital transformation every chance of success.

Comments